Sariska Tiger Reserve National Park

Wild animals (like humans) behave differently when they feel themselves unobserved. They seem to feel that way at water holes in Sariska Tiger Reserve National Park at night—resting, drinking, interacting, nursing and nuzzling young ones, courting, mating, grooming themselves—and others—sometimes killing for a meal or to eliminate a rival.

It is a special world seen from the darkness.

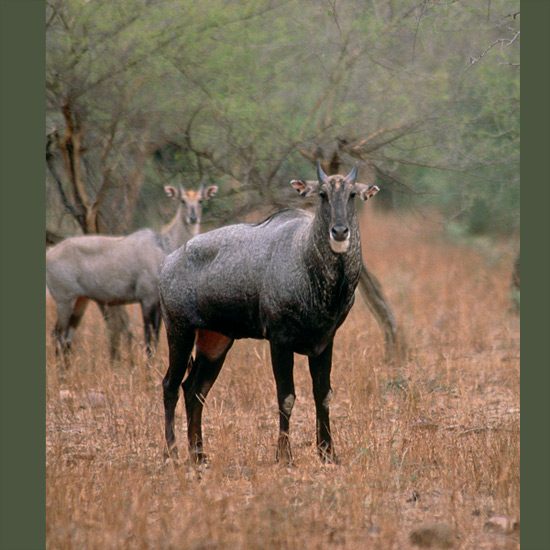

Fruit-drinking bats flutter in for a sip. Fish-eating owls swoop down, their super-keen senses telling them that dinner is there for the taking. An occasional rare, shy, solitary caracal is so quiet it can pass unnoticed. Wild boars snuffle through leaves. Horselike nilgai or blue bulls drop to their knees to settle disputes without undue violence. Touchy porcupines lumber along, seeming to feel invulnerable (without justification; they are widely preyed on, though their needles can make fatal meals).

Tigers roar their assertion that they are at the top of the food chain, unchallenged even by the leopards and certainly not by nervous jackals, hyenas, or little jungle cats.

Sariska’s 308 square miles (800 km2) of rolling wooded canyons surrounded by starkly dramatic mountain crags, originally shooting preserve of the Alwar ruling family, came under Project Tiger in 1979. It has always been good tiger terrain, having the habitat and prey base these magnificent endangered animals require—chital or spotted deer, sambar, nilgai, chousingha, and other smaller species.

Wildlife, including interesting bird species, can be seen in daytime too along the good road network. There are ninth-century ruins of Shiva temples (one still used by pilgrims) and a Kankwari fort.

Best times are November–March (April–June is interesting but hot). Accommodations include a forest bungalow, rest house and, at the park entrance, a converted royal palace, now a hotel. Rentals are available for blinds or hides for night viewing at water holes (take a sleeping bag and go by early afternoon). Four-wheel-drive vehicles for hire. Threats include mining pressure (sometimes illegal) and overvisitation.

Click image for details.

Advertisement