Canadian Rockies

The Canadian Rockies were “the shining mountains” to aboriginal people astonished at glistening glaciers and rocky snowcapped peaks which arose from sea-bottom sediment 1.5 billion years ago. But it is the grizzly bears, elk, mountain goats, wolves, moose, and eagles that have made this dramatically beautiful place world-renowned.

This U.N. World Heritage Site is one of the world’s largest protected mountain landscapes—a designated Natural Region extending over some 69,480 square miles (180,000 km2) and a dozen or so protected wilderness areas, including Waterton Lakes adjoining U.S. GLACIER NATIONAL PARK (see p.479). The core site covers some 8,000 square miles (23,010 km2) including Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, and Yoho Canadian National Parks, and three British Columbia provincial parks.

Hundreds of jewel-like blue-green ponds and lakes owe brilliant hues to eroded silt from milky streams fed by glaciers constantly grinding away at the 11,000-foot (3,355-m) continental divide. Largest of ice concentrations descending from this ancient spine is the great Columbia Icefield, covering 130 square miles (325 km2) and estimated to be more than 1,000 feet (305 m) thick, source of rivers flowing to three oceans.

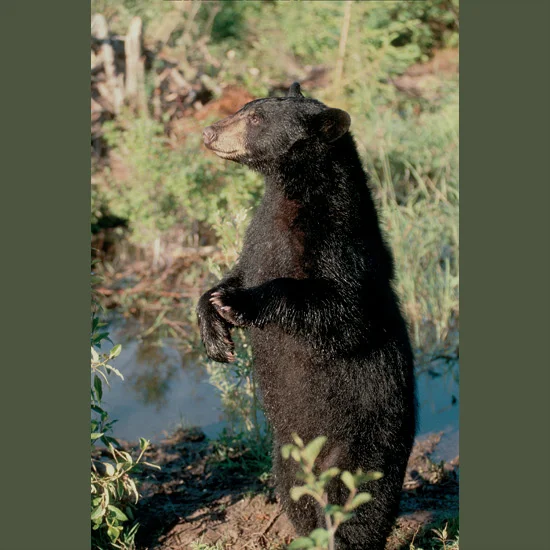

Coyotes, black bears, bighorn and Dall sheep, rare woodland caribou, and others—69 mammal species—wander about as if they own the place, which in a sense they do. Bighorn sheep rest alongside Highway 16 east of Jasper, seemingly unencumbered by spiraled horns which grow to 45.3 inches (115 cm) and weigh 33 pounds (15 kg). Their white-pelted cousins, Dall sheep, lounge alongside the Alcan highway near Summit Lake.

Mountain goats lick salty rocks near trails below Mount Wardle in Kootenay National Park. Elk in the Canadian Rockies were almost hunted to extinction early in the 20th century, but have thrived since reintroduction in 1917 and now nibble grassy lawns and shrubbery in and around the park.

Predators tend to be more retiring; they include lynx, red foxes, and small but fierce wolverines, solitary, stealthy stalkers of snowshoe or varying hares but capable of bringing down a deer. Their fur sheds ice crystals—handy up here. Prickly prey for all are slow-moving porcupines, protected by climbing agility and some 30,000 quills which are soft at birth but harden to dangerous spines within an hour.

Western jumping mice, yellow-pine chipmunks, meadow voles, and other small rodents are prey for glossy-brown martens, mink, and short-tailed weasels which become snowy ermines in winter. (Weasels don’t easily catch an alert jumping mouse, which can leap up to 10 feet/3 m in a single bound.)

Bald eagles cruise ridge lines. Northern harriers patrol meadows for ground squirrels. Ospreys dive for cutthroat trout. River otters streak after them underwater. Loons call eerily. Up to 8,000 golden eagles move north overhead from March to May, joined by smaller numbers of other raptors, and pine siskins, bohemian waxwings, and ruby-crowned kinglets begin to move in.

The Canadian Rockies are renowned for alpine-zone species: gray-crowned rosy finches, golden-crowned sparrows, pipits, approachable willow and white-tailed ptarmigans, whose plumage changes to white every fall.

Dapper western grebes pair up for graceful springtime courtship ballets. Barrow’s goldeneyes lay blue-green eggs in hollow tree stumps. Belted kingfishers’ rattling cries are heard along streams. American dippers, our only aquatic songbirds, dive into fast-flowing streams and literally fly underwater to catch tiny fish, able to do this in current too swift and water too deep for humans to stand.

Black-billed magpies socialize raucously. Colorful varied thrushes are almost as common but secretive. More easily spotted are red and white-winged crossbills and many bright warblers— yellow, yellowthroat, Wilson’s, Macgillivray’s, Townsend’s, Tennessee.

Great horned owls announce nightfall, echoed by little boreal owls’ winnowing snipe-like “hoo-hoo-hoos.”

The Rockies have 277 bird species—but only one kind of turtle, two toads, four snakes, and six frogs, one of which clings to life above the tree line, freezing solid every winter. Built-in antifreeze enables it to thaw undamaged every spring.

Ninety kinds of butterflies rush urgently through brief summer life cycles among dazzling valleys of blue harebells, orange arctic poppies, pink alpine moss-campions. In the fall, valleys are filled with ripening blueberries, black bears’ favorites. September hillsides shimmer with golden larches.

Best way to see everything can be simply to stop and sit quietly and observe. Moose come out to nibble willow shoots at the bog’s edge. A curious weasel might sniff your shoes, a mountain chickadee land on your head. One woman, watching motionless, had a beaver come curl up in her lap.

The value of saving these matchless lands can be seen by comparing them with surrounding areas which, unprotected, have been threatened or laid waste by logging, oil and gas exploration, dam and road construction, deleterious ranching and agricultural practices, and unchecked resort or residential housing and commercial development. But some of the greatest wildlife hazards are inside the parks, where careless motorists kill hundreds of animals every year.

Best times are late June–mid-September, but many prefer late September–early October, with fewer visitors, though some facilities close then. Weather is cool but still pleasant. Variable temperatures can require jackets even in summer. Fall colors are stunning. Most parks are open all year for wildlife-viewing.

Click image for details.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

CANADIAN ROCKIES as well as...

Waterton Lakes

YOHO NATIONAL PARK as well as...

Mount Robson Provincial Park

Advertisement